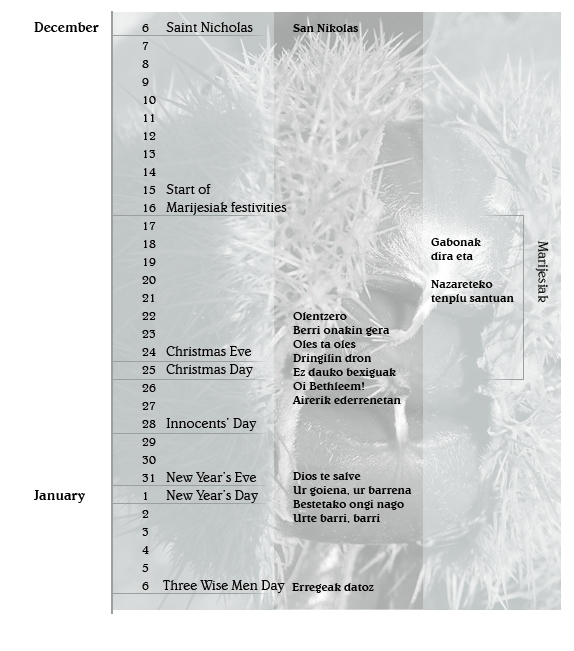

Here follows a calendar of this time of the year featuring the main celebrations and the repertoire of traditional musical pieces selected for the present book of songs

Since the beginning of time, human beings have made every effort to comprehend and find reason for events that take place around them and the relationship between themselves and the surrounding world. Individuals have for the most part made use of certain general outlooks on life and categorical beliefs in order to interpret everyday experiences within an orderly universe.

Due to the continual interaction of men and women with the realm of Nature, the natural yearly circle of the seasons, a process that repeats itself year after year, has widely been taken as a reference and a guideline.

We shall take these first-hand experiences as a standpoint for the study of the traditional customs in Euskal Herria during the winter term, observed in the past and which still survive to this day.

We shall take these first-hand experiences as a standpoint for the study of the traditional customs in Euskal Herria during the winter term, observed in the past and which still survive to this day.

First of all, and as a matter of fact, we should mention that many cultures around the planet, and according to the natural course of the solar day, hold observance to the winter solstice and the summer solstice as indicators directly related to the natural circle of the Sun. It is a traditionally well-known astronomical subject that precise knowledge of the Sun path as the Earth rotates and the length of daylight determine the solstices, which in turn are connected with the seasons. Here follows Manuel Lekuona’s explanation of the phenomenon:

“They observed [the ancient Basque people or jentillak] that the Sun rised and set at different points above the horizon, each time a little further north or further south (comparable to olloaren arra, a chicken foot, or ardiaren xaltoa, a sheep jump). They saw for themselves that as the Sun moved north the days became longer, and as it travelled south, the period during which sunlight reached the ground gradually shortened.

Moreover, they realized that in its excursion the Sun appeared to come to a stop before reversing direction: its path lengthened after having shortened and shortened after having lengthened.

The word solstice is derived from the Latin solstitium, solsticio in Spanish and refers to the Sun standing still (…). Old-time Basque shepherds were well aware of the above-mentioned phenomenom that took place in the skyline. Everytime it happened, the Sun was honoured in solemn ceremony (the Sun was said to join in the dance at nightfall). That is the occasion and mystery celebrated by ancient Basque shepherds on Saint John’s Eve. A pre-Christian ritual, a pure feast recalled by old songs that are still heard in our farmhouses. The Olentzero songs of the Bidasoa area are just an example”.

The word solstice is derived from the Latin solstitium, solsticio in Spanish and refers to the Sun standing still (…). Old-time Basque shepherds were well aware of the above-mentioned phenomenom that took place in the skyline. Everytime it happened, the Sun was honoured in solemn ceremony (the Sun was said to join in the dance at nightfall). That is the occasion and mystery celebrated by ancient Basque shepherds on Saint John’s Eve. A pre-Christian ritual, a pure feast recalled by old songs that are still heard in our farmhouses. The Olentzero songs of the Bidasoa area are just an example”.

The two solstices mark the seasons of the year, and the social and family celebrations arising around them are widespread around the four corners of the Earth. It is also by all means common to embrace the use of other natural elements such as fire and water for such customs and rituals.

Apart from the above-mentioned importance of the Sun path, in some cultures the significance of the phases of the Moon is also underlined. In the Basque culture, only a few aspects featuring the influence of the Moon and its phases have survived over the centuries, such is the case of Easter and the festive season of Carnival. The major role played by the Church in western cultures with respect to the Moon and its bearing on popular traditions needs to be taken into consideration. Christianism has often adopted and made its own previously established occasions and ceremonial rituals fitting and adjusting them within the prescribed liturgical calendar and conventions. This practice is evident in the festivities we shall be looking at: the feast of Saint Nicholas, Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, New Year, Three Wise Men Day…

Therefore, the traditional Christmas celebrations in our culture show a good mixture of ancient or pre-Christian features together with elements that are distinctive of the Christian approach.

Taking into account the geographical location of Euskal Herria, it is certainly easy to distinguish the continental side of the country from its peninsular area only by looking at its orography and hydrography. Besides, a quick examination of its natural features shows us a coastal region streching along the Gulf of Bizkaia and an extension of land heading towards the Mediterranean Sea.

The climate does not generally present harsh changes from the summertime to the winter period. The seashore counts with a rainy and humid climate, whereas the inland region is drier, and there the winter and the summer seasons are more clearly differentiated. The people and the types of settlement in both territories are also different. With the exemption of towns or dwellings erected for particular reasons, in times past single houses scattered in the valleys and groups of houses were more frequent in central areas.

Taking this objective information as the starting point for our study, we shall find it easier to understand the origins of some of our winter season festivities.

In winter the highly treasured farm foods were put away in storehouses and attics. The crops: wheat, maize, garden vegetables… had been harvested during the autumn. Besides, many more fruits were available in the farm: chestnuts, walnuts, hazelnuts… From Saint Martin’s Day onwards, after pig slaughtering, the pork meat was preserved, some cuts were salted and stored in cages and others hung in the kitchen, all ready to be enjoyed. Grape and apple presses kept on processing the fruit, and casks and barrels were brimming over with wine.

At this time of the year, and following ancient laws, folks were ready to give aid to the poor. Within a traditional social system, those in need had the right to beg for shelter or food, and those who possessed the means were obliged to help according to basic human laws. There existed a sense of brotherhood and fellowship amongst the people.

Nowadays economic resources tend to be the defining characteristic of social units. In the past, though, people were categorized by their responsibilities around the house and towards the other members of the group rather than by lineage or occupation. Following this criterion, we can talk about a number of traditional social groups which do not coincide with modern types: children (who lived under parental protection), young people (who worked in the house but did not enjoy economic freedom), married people (who joined in matrimony in order to create and sustain their own family unit), old people (who lived in the house but would not be in charge of household chores although often cared for the young ones)…

The category of the youth is socially most interesting. Young males, in particular, took a great measure of responsibility for numerous community-building initiatives (the organization of village or neighbourhood annual festivities, security and control issues, and so forth). However, they did not count with economic support, and that is why they would often go door-knocking, singing and asking for a voluntary donation. Moreover, on their tours young boys took advantage to pay court to young girls in marriageable age.

The verses sung nowadays by children in their money-asking tours are very similar to those performed by young men in the past. According to some experts, the former might well be an evolution of the latter.

Let us bear in mind the brief explanation provided above, which should be helpful for the understanding of the following songs and special practices that take place in diverse locations of the Basque territory.