The prime objective of the Urte-sasoiak collection is to make it known to the public the ever-present tight connection in Euskal Herria between the traditional seasons of the year and a set of customs that still are very much alive.

The prime objective of the Urte-sasoiak collection is to make it known to the public the ever-present tight connection in Euskal Herria between the traditional seasons of the year and a set of customs that still are very much alive.

This second booklet deals with another special set of celebrations that follow Christmastide; namely, Carnival and other associated festivities.

This is the heart of winter, as the words of a song included in this collection state.

In these traditional celebrations, the importance of the solar calendar is extremely relevant (in a similar way as the winter and summer solstices mark Christmas time and Saint John’s Day festivities). On top of it, and as a novelty, the influence of the lunar cycle comes to the fore at Carnival. Besides, there are certain days at the beginning of February abounding with beautiful and exclusive customs and rituals. Both the Sun and the Moon phases calendars will sometimes overlap.

The material has been compiled under the title Hou Pitxu hou!. The Maskarada is well known amongst the Basque people and is, perhaps, our finest, most colourful, refined and elaborated example of popular ritual. Without any doubt, Pitxu is the Maskarada character that best and clearest embraces the spirit of Carnival. For that, we shall take it as the stardard bearer or symbol of the whole cycle.

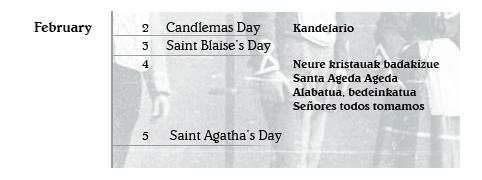

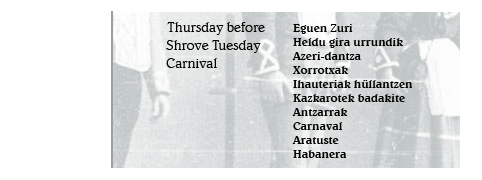

Here follows a calendar featuring the main celebrations preceding Shrovetide and the repertoire of traditional musical pieces selected for the present book of songs.

The Carnival calendar chages from year to year and is determined by Easter and the Lenten period.

Easter Day is annually observed on the Sunday that succeeds the first full moon after the vernal equinox. The vernal equinox has traditionally been celebrated on 21 March, and after the Moon appears with the whole disc illuminated, it needs 14 days to complete its cycle. Therefore, Easter Sunday can at the earliest fall on 22 March and at the latest on 25 April.

On account of that, the Basaratoste barbecue feast is celebrated on 25 January at the earliest and on 28 February at the latest, the Sunday before Shrove Tuesday on 1 February at the earliest and on 7 March at the latest, Ash Wednesday on 4 February at the earliest and on 10 March at the latest, and so on.

These are the songs and dances selected for the Carnival festive season:

In western tradition, once Christmastide is over, there is another important period of popular festivities: the Carnival cycle.

Julio Caro Baroja claimed that these second cycle was without any doubt linked to Lent in its origins, and that the particular events that have survived to the present time started to take shape in the Middle Ages. In any case, the truth is that features of Christianity often blend in with pre-Christian elements from an ancient pagan life.

Besides, it is well worth mentioning the breach that carnivalization itself represents from a social point of view.

At Carnival a rupture of time takes place, and the interruption of the continuous passing of time brings about a weakening of the social laws in force. During this time it becomes rightful then to break certain laws and to turn upside down the prescribed order within social classes. At Carnival what is usually venerated becomes condemned, and what is normally scorned turns to be praised.

This disruption is more than evident in our popular celebrations, and masks, laughter, dances, songs and other numerous performances displayed throughout the territory are good proof of it.

Nevertheless, there is a time limit to the breach of law: Ash Wednesday. This day marks the start of the Lenten period and, with it, the return of social order and the commitment to penance, fasting and penitence until Easter Eve.

Close to the Carnival time, and perhaps somehow linked to it, there are in Euskal Herria a good number of unique events that take place at the beginning of February. In spite of people nowadays relating them to Christian practices and symbols, the above-mentioned set of events and rituals piled up in such a short time deserve some consideration.

They might not constitute a solid unit on the whole; they might be little humble customs that are often practised without premeditation; however, those customs pertain, by and large, to the realm of the house and the family, and are of great value for the understanding of the traditional viewpoint about global matters. Despite the fact that at a glance one might be tempted to include such festivities in the liturgical calendar, they still retain a trace of ancient scent.